by Rabbi Jeffrey Miller

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed here are that of the writer and do not necessarily represent the views of the Union for Traditional Judaism, unless otherwise indicated.

“Where words fail, music speaks.”

Hans Christian Andersen

There is no good time for tragedy to strike, but there are times when tragedy is downright inauspicious. Such is the case with the deaths of Nadav and Avihu, the eldest sons of Aharon. Aharon and his sons had just been invested with the priesthood and were about to formally dedicate the Mishkan. For reasons that are not made clear, Nadav and Avihu “each took his fire pan, put fire in it, and laid incense on it; and they offered before God an alien fire, which had not been commanded of them.”[1] Their punishment was immediate, harsh, and unappealable:

וַתֵּ֥צֵא אֵ֛שׁ מִלִּפְנֵ֥י ה וַתֹּ֣אכַל אוֹתָ֑ם וַיָּמֻ֖תוּ לִפְנֵ֥י ה

And fire came forth from before God, and devoured them, and they died before God.[2]

In a departure from the rule that a sinner must be duly warned before he can be subject to the death penalty, Nadav and Avihu are neither warned before they sinned nor before the death sentence was imposed upon them. So unsettling is this Biblical anecdote that the Sages dissected every word of it, as well as the surrounding texts, in the hopes of making sense of it. Chazal wanted to uncover the motives behind (and nature of) the “strange” or “foreign” fire, and the seemingly disproportionate death sentence that was so swiftly decreed and carried out from on High.

This was not merely an academic exercise. On the contrary, Chazal’s thirst to understand this story was born out of an existential necessity. Simply put, they sought proof – reassurance – that God is not arbitrary, capricious, and devoid of compassion. They (and we) struggle to find structure and order in the senseless, chaotic world that so often seems inhumane. They – and we – need the world to be just and fair rather than haphazard and hateful.

That the two brothers were involved in improper behavior is not really in dispute. Their fire was described as אֵ֣שׁ זָרָ֔ה, “alien” in nature, and their sacrificial offering was a clear deviation from the scheduled program. A few Torah commentators concluded that the boys were well-intentioned but reckless. Prof. Edward Greenstein[3] cites Philo of Alexandria, an early exegete, who suggested that Aharon’s sons acted benignly, having been “swept up by the excitement of the dedication ceremony.”

Philo’s approach offers a profound lesson that can be summed up by the well-known aphorism that the “road to Hell is paved with good intentions.” One who commits a grave sin cannot escape culpability by raising the defense that he was merely swept up in the passion of the moment. This principle applies with even greater force when the perpetrator is not a faceless, nameless member of the crowd – an “extra”- but rather the star of the show, or at least a co-star, like the newly minted Kohanim, Nadav and Avihu.

Many of the classical theologians imputed various degrees of malice to the actions of Nadav and Avihu. Rashi[4], for example, posited that Nadav and Avihu brought their sacrifice while in a drunken stupor. Bar Kappara offered four separate possibilities[5], among them that Nadav and Avihu trespassed into the Kodesh Kodashim (Holy of Holies) without authority.

Others suggested that by bringing the sacrifice themselves, they usurped the honor that was due to their father Aharon, the anointed Kohen Gadol. In doing so, Nadav and Avihu violated the fundamental commandment of Kibbud Av (honoring one’s father). If the reward for that mitzvah is a blessing of a long life[6], then the converse should be also true. The sons were struck down because they publicly humiliated their father.

With an irony that is found in many Torah stories, Nadav and Avihu became the very “sacrifice” that they had intended to offer. And after their fiery deaths came the messy task of removing their corpses from the sacred Tabernacle. For that job, Moshe summoned his cousins Mishael and Elzaphan[7]:

וַיִּקְרָ֣א מֹשֶׁ֗ה אֶל־מִֽישָׁאֵל֙ וְאֶ֣ל אֶלְצָפָ֔ן בְּנֵ֥י עֻזִּיאֵ֖ל דֹּ֣ד אַהֲרֹ֑ן וַיֹּ֣אמֶר אֲלֵהֶ֗ם

קִ֠רְב֞וּ שְׂא֤וּ אֶת־ אֲחֵיכֶם֙ מֵאֵ֣ת פְּנֵי־הַקֹּ֔דֶשׁ אֶל־מִח֖וּץ לַֽמַּחֲנֶֽהMoses called Mishael and Elzaphan, sons of Uzziel the uncle of Aaron, and said to them, ‘Come forward and carry your kinsmen away

from the front of the sanctuary to a place outside the camp.’

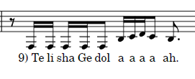

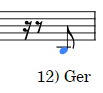

The word קִ֠רְב֞וּ is unusual in that it is chanted with two distinct musical cantillations: the Telisha (תְּ֠לִישָא גְדוֹלָה) and the Gershayim (גֵּרְשַׁ֞יִם). There are only eight places in all of the Torah where these two tropes appear over adjacent words[8]. And there are only two places in all of Chumash where these two notes appear on a single word[9]:

The Hebrew word for the Torah’s musical notes (called trope or cantillation) is ta’am (pl. te’amim). It means, in various contexts, “flavor”, “taste”, “sense”, or “reason.” The cantillation of Torah was not added just for dramatic effect, punctuation, or emphasis. Nor was it added to embarrass thirteen-year-old boys whose pubescent voices struggle to hit the tones without cracking.

According to the Talmudic Sage Rabbi Yitzhak[10], the Torah’s musical score is sacred, having been revealed to Moshe along with the written text of the Torah. Rav Ika bar Avin[11] commented that one cannot truly understand the meaning of the Torah without also knowing the accompanying sheet music. L’havdil elef havdalot, most of us would agree that we cannot fully fathom an artist’s song by just reading her lyrics. The music does not just compliment the words; it elucidates them.

Many of the cantillations are grouped in distinct families, causing the Torah to be chanted in familiar strings of notes. The Telisha and the Gershayim are different; they are not part of a family. Rather, they are both ‘loners’. Each has the effect of breaking up the flow of the Torah’s song and making the words ‘pop’. Indeed, their very names hint at their function. Gershayim[12] means ‘expulsion’ or ‘divorced’. The word upon which the Gershayim is placed is sung alone, divorced from the other words in the verse. Similarly, Telisha comes from the root word meaning ‘detached’ because he, too, does not play well with the other tropes in the verse.

But that is where the similarity ends. I confess that I am tone-deaf, but even with my physical challenge, I can tell that the Telisha (תְּ֠לִישָא גְדוֹלָה) and the Gershayim (גֵּרְשַׁ֞יִם) do not belong next to each other, let alone atop the same word.

The Telisha rises up ever so slightly before dipping down. This emotes a somber mood.

The Gershayim rises up and stays there, thus expressing hope.

Something subtle yet remarkable is afoot. קִ֠רְב֞ו, “come forward”. Moshe beckoned his reluctant cousins by uttering a nuanced word with two inconsistent intonations. He invited Mishael and Elzaphan to fulfill the sacred duty called חסד של אמת (“Kindness of Truth”). This is a euphemism for collecting, caring for, and burying, the deceased.

In rabbinic literature, when the two incongruous words of kindness (חסד) and truth (אמת) are juxtaposed, an entirely new concept is created. ‘Truth’ is the fate that befalls all mankind. “Kindness of truth” is the selfless act of caring for those who have died.

Similarly, קִ֠רְב֞ו, with its two incongruent musical notes, no longer simply means “come forward.” With a stark musical arrangement, Moshe Rabbeinu implied that the mood in and around the Israelite camp was chaotic. Perhaps Aharon’s sons were guilty of a great crime and were punished accordingly.

Perhaps they got caught up in well-intentioned religious ecstasy. We just do not know.Perhaps Mishael and Elzaphan were afraid that they, too, would be burned alive. Or perhaps they were squeamish. Or perhaps they were distraught. Regardless, they were hesitant to assume the sacred responsibility of חסד של אמת until coaxed by Moshe Rabbeinu with a tone in his voice that simultaneously encouraged both duty and honor.

In recounting Noach’s birth, the Torah tells us that his father, Lemech (prophetically) chose a name that his child would one day come to exemplify:[13]

וַיִּקְרָ֧א אֶת־שְׁמ֛וֹ נֹ֖חַ לֵאמֹ֑ר זֶ֞֠ה יְנַחֲמֵ֤נוּ מִֽמַּעֲשֵׂ֙נוּ֙ וּמֵעִצְּב֣וֹן יָדֵ֔ינוּ מִן־הָ֣אֲדָמָ֔ה אֲשֶׁ֥ר אֵֽרְרָ֖הּ ה׃

He named him Noach, saying, “This one will comfort us from our work and the labor of our hands, from the ground which Hashem has cursed.”

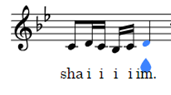

Just as we saw with Nadav and Avihu, and Mishael and Elzaphan, the use of the Telisha (תְּ֠לִישָא גְדוֹלָה) and the Gershayim (גֵּרְשַׁ֞יִם) over the word “this one [Noach]” is intended to emphasize that Noach’s life as a survivor and savior can only be understood in the context of the cruelty that marked the age of the Deluge. In Noach’s generation, there was very little kindness (חסד) or truth (אמת). But there was Truth in the form of Divine Judgment coupled with Celestial Kindness in the form of salvation and renewal.

Just before Moshe Rabbeinu called upon Mishael and Elzaphan, he tried to comfort his grieving brother Aharon:

וַיֹּ֨אמֶר מֹשֶׁ֜ה אֶֽל־אַהֲרֹ֗ן הוּא֩ אֲשֶׁר־דִּבֶּ֨ר ה ׀ לֵאמֹר֙ בִּקְרֹבַ֣י אֶקָּדֵ֔שׁ וְעַל־פְּנֵ֥י כׇל־הָעָ֖ם אֶכָּבֵ֑ד וַיִּדֹּ֖ם אַהֲרֹֽן׃

Then Moses said to Aaron, “This is what God meant by saying: ‘Through those near to Me I show Myself holy, And gain glory before all the people.’

And Aaron was silent.

Many explanations are proffered for Aharon’s silence in response to Moshe’s cryptic words, but the simple truth is that in times of grief, words are inadequate to express the inchoate emotions of the heart. “A picture may say a thousand words”, but a melody unlocks the chamber where those words are buried.

That is why God endowed us with harmony and music.Shabbat Shalom!

[1]. Lev 10:1.

[2]. Lev. 10:2.

[3]. https://www.thetorah.com/article/the-incident-of-nadav-and-avihu.

[4]. Rashi on Vayikra 10:2, quoting Vayikrah Rabbah 12:1.

[5]. Vayikra Rabba 20:8-10.

[6]. Shemot 20:11. כַּבֵּ֥ד אֶת־אָבִ֖יךָ וְאֶת־אִמֶּ֑ךָ לְמַ֙עַן֙ יַאֲרִכ֣וּן יָמֶ֔יךָ עַ֚ל הָאֲדָמָ֔ה אֲשֶׁר־ה אֱלֹקיךָ נֹתֵ֥ן לָֽךְ

[7]. Vayikra 10:4.

[8]. Bereishis 18:28, 30 and 32; Shemot 25:33, 33:12 and 37:19; and Devarim 26:12 and 27:12.

[9]. These two notes appear on a single world three other times in Tanach: Kings II 17:13 (שֻׁ֠֜בוּ), Yechezkel 48:10 (וּ֠לְאֵ֜לֶּה), and Tzefania 2:15 (זֹ֠֞את).

[10]. Nedarim 37b,רַבִּי יִצְחָק: מִקְרָא סוֹפְרִים, וְעִיטּוּר סוֹפְרִים, וְקַרְיָין וְלָא כְּתִיבָן, וּכְתִיבָן וְלָא קַרְיָין — הֲלָכָה לְמֹשֶׁה מִסִּינַי.

[11]. Id., ״וַיָּבִינוּ בַּמִּקְרָא״ — זֶה פִּיסּוּק טְעָמִים

[12]. The suffix “ayim” means “two” because the note, depicted as a double Gersh, looks like a quotation mark with two apostrophes.

[13]. Gen. 5:29.

Enjoying UTJ Viewpoints?

UTJ relies on your support to promote an open-minded approach to Torah rooted in classical sources and informed by modern scholarship. Please consider making a generous donation to support our efforts.