by Rabbi Noah Gradofsky

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed here are that of the writer and do not necessarily represent the views of the Union for Traditional Judaism, unless otherwise indicated.

Shoftim 5782 – Meaning of Halakhah.

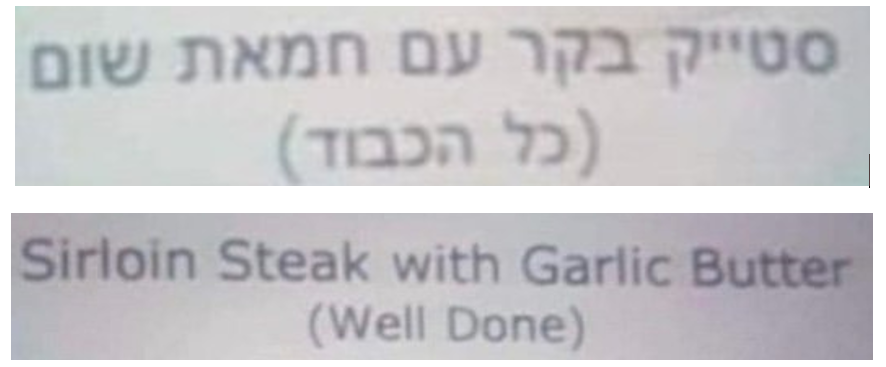

As anyone who has ever read an English menu in Israel can tell you, translations can be difficult. In fact, I just came across a fun Twitter thread featuring some great translational mishaps.

For example, one menu, I suppose originally written in English, offered a steak “כל הכבוד.” The phrase כל הכבוד is a common congratulatory phrase in Hebrew, and one might think that the chef was very proud of her steak. But it turns out that no, the writer of the menu just wanted you to know that the steak would be כל הכבוד, well done!

Another sign wanted to warn people not to smoke by warning them that if they did so, they were in line לקנס – for a fine. But instead, the translation ended up encouraging smokers by telling them in English “Violators will be fine.”[1]

Understanding something in another language is even more difficult when that language is borrowing from another language. For instance, I spent years wondering why Israel’s telecom company had a logo featuring the number 8.

I mean, a telephone has all 10 numbers on it. What was special about the number 8? I am a little bit ashamed to say that I wondered this quite a few occasions until eventually I figured out that in fact, that big symbol was not the number 8, but a B for Bezek. Oops.

My absolute favorite story along these lines, though admittedly not a story that will make anyone confuse me for an intelligent person, is the time I looked on for a while in wonderment at a sign over a store in the distance with the Hebrew letters spelling out “Sofer Meraket.” Now, I knew that the word sofer can be a scribe or perhaps someone who sells books or other religious articles. But I had no idea what meraket was and how it might modify the word sofer. I’m glad to say this one didn’t take me as long as the Bezek logo took me, but I’m a little embarrassed to say that actually, the sign did not say Sofer Meraket, but, rather סופרמרקט – supermarket.

Well, words are often difficult to understand. This is true even about words we’ve known and used for a long time. There are many words in the biblical and rabbinic lexicon whose meaning, frankly, we’re not so sure of. Surprisingly, one such word is a word we use all the time and that stands at the very core of Jewish practice – halakhah. Most of us are familiar with the idea that the term halakhah came from the same words as lalekhet, to walk, and means something along the lines of “the path.” But the truth is, we don’t know where the word halakhah comes from. In a roundabout way, a midrash on this week’s Torah portion may provide an important hint for what the word halakhah means.

מנין למחליף דברי רבי אליעזר בדברי רבי יהושע ודברי רבי יהושע בדברי רבי אליעזר ולאומר על טמא טהור ועל טהור טמא שהוא עובר בלא תעשה תלמוד לומר לא תסיג גבול רעך.

From what text do we know that one who switches the words of Rabbi Eliezer with the words of Rabbi Joshua, and the words of Rabbi Joshua for the words of Rabbi Eliezer, or one who says something that is impure is pure or that something that is pure is impure, that person has violated a prohibition? Scripture states: “Do not move your neighbor’s landmarks.”[2]

The verse that this midrash is based on, Deuteronomy 19:14, literally deals with moving boundary markers. What’s that got to do with someone who misrepresents halakhah by declaring something pure that is impure or vice versa?

The teacher of many of my teachers, haGaon Rabbi Shaul Lieberman provided an understanding of the word halakhah that I find compelling.[3] He notes that in the book of Ezra[4] there is reference to a tax called הלך halakh, apparently related to the Babylonian term ilku. Rabbi Lieberman notes an ancient document referencing a land tax, i.e. a tax based on the boundaries of one’s property, calledהלכא halakha. Based on this, Rabbi Lieberman concludes that halakhah literally means a boundary, and hence comes to mean a statement of legal principle. It is here that Rabbi Lieberman reminds us of that strange midrash about how deliberately changing the halakhah violates the Torah’s prohibition against moving boundary markers. As an interesting side note, Rabbi Daniel Rosenberg pointed out to me that laws would often be posted at the boundaries of territories, so that perhaps the association of law with halakhah, boundaries, is similar to how another word for law, חוק hok derives for the words “chisel,” since laws were often carved in stone.

Years ago, a colleague of mine, Rabbi Wayne Allen, delivered a lecture about Rabbi Lieberman’s understanding of the word halakhah.[5] He noted that while the term certainly has some sense of fixture, the term “boundary” also provided for the possibility of a range of options within those boundaries. I think this is a very powerful and different way to think about halakhah. Instead of halakhah representing a straight-and-narrow path, it instead presents a range of options, an area within which we can choose to operate. There are boundaries, but there is also room for different interpretations and for personal and community minhagim (customs) and therefore different ways to live up to what God expects of us in different ways. Similarly, my teacher Rabbi Alan Yuter talks about how there are three classes of law in Jewish law – there is that which is חובה, obligation and that which is אסור, forbidden. Between those two poles, there is רשות, rights – i.e. the range of behaviors that we may choose from.

In the Talmud in Berakhot (8a), Rabbi Hiyya bar Ami says in the name of Ula:

מיום שחרב בית המקדש אין לו להקדוש ברוך הוא בעולמו אלא ארבע אמות של הלכה בלבד.

From the day that the Holy Temple was destroyed, the Holy One, Blessed is He has in this world only the four amot of halakhah.

When our mind’s eye thinks about Ula’s teaching, I assume that we should be picturing a square, much like the square within which one may carry in a public domain on Shabbat.[6] Hence, Ula gives us the beautiful metaphor that we find God in our lives by doing our best to stay within the boundaries of halakhah.

For me, this picture of halakhah as much liberating than it is limiting. Halakhah gives us the opportunity to find our place within the Jewish world. We all have different preferences for how we want to live our lives, what jobs we seek, what company we keep, what we do to relax. We also face different challenges. Halakhah provides some dicates, but more importantly it provide us with guidelines for how we can be who we want to be, achieve what we can, and respond to our many challenges, all while keeping ourselves within the metaphorical four amot of halakhah wherein the divine resides.

As the High Holidays approach, I hope that we can all use this period of time to find our place not on a path that is dictated to us, but exactly where we are meant to be within the four amot of halakhah.

[1] Through some google searching it looks to me like this picture is manipulated (see e.g. here) and there used to be a d at the end of the line which is now made to look like a period … but this is still funny and good enough for some humor at the beginning of a dvar Torah.

[2] Sifre Devarim 188.

[3] Lieberman, Helenism in Jewish Palestine p. 83 footnote 3.

[4] E.g. Ezra 4:13.

[5] For video of this lecture, see Rabbi Wayne Allen’s lecture at https://utj.org/viewpoints/videos/the-term-halakhah-and-its-implications-for-jewish-life-lieberman-yahrzeit-lecture/ .

[6] See Rambam Mishneh Torah, Shabbat 12:15 and following, Shulhan Arukh Orah Hayyim 349:1 and following.

Enjoying UTJ Viewpoints?

UTJ relies on your support to promote an open-minded approach to Torah rooted in classical sources and informed by modern scholarship. Please consider making a generous donation to support our efforts.